There was also a time when, wandering through museums, I would stop to face and question the Saint Georges and their dragons. The paintings of Saint George have this virtue: you can tell the painter was pleased to have to paint a Saint George. Because Saint George can be painted without believing too much in him, believing only in painting and not in the theme? But Saint George’s position is shaky (as a legendary saint, too similar to the Perseus of the myth; as a mythical hero, too similar to the younger brother of the fairy tale), and painters always seem to have been aware of this, so they always looked on him with a somewhat “primitive” eye. But, at the same time, believing: in the way painters and writers have of believing in a story that has gone through many forms, and with painting and repainting, writing and rewriting, if it was not true, has become so.

There was also a time when, wandering through museums, I would stop to face and question the Saint Georges and their dragons. The paintings of Saint George have this virtue: you can tell the painter was pleased to have to paint a Saint George. Because Saint George can be painted without believing too much in him, believing only in painting and not in the theme? But Saint George’s position is shaky (as a legendary saint, too similar to the Perseus of the myth; as a mythical hero, too similar to the younger brother of the fairy tale), and painters always seem to have been aware of this, so they always looked on him with a somewhat “primitive” eye. But, at the same time, believing: in the way painters and writers have of believing in a story that has gone through many forms, and with painting and repainting, writing and rewriting, if it was not true, has become so.

Even in the painters’ pictures, Saint George always has an impersonal face, not unlike the Knight of Swords of the cards, and his battle with the dragon is a scene on a coat of arms, fixed outside of time, whether you see him galloping with his lance at rest, as in Carpaccio, charging from his half of the canvas at the dragon who rushes from the other half, and attacking with a concentrated expression, his head down, like a cyclist (around, in the details, there is a calendar of corpses whose stages of decomposition reconstruct the temporal development of the story), or whether horse and dragon are superimposed, monogram-like, as in the Louvre Raphael, where Saint George is using his lance from above, driving it down into the monster’s throat, operating with angelic surgery (here the rest of the story is condensed in a broken lance on the ground and a blandly amazed virgin); or in the sequence: princess, dragon, Saint George, the animal (a dinosaur!) is presented as the central element (Paolo Uccello, in London and Paris); or whether Saint George comes between the dragon in the rear and the princess in the foreground (Tintoretto, London).

In any case, Saint George performs his feat before our eyes, always closed in his breastplate, revealing nothing of himself: psychology is no use to the man of action. If anything, we could say psychology is all on the dragon’s side, with his angry writhings: the enemy, the monster, the defeated have a pathos that the victorious hero never dreams of possessing (or takes care not to show). It is a short step from this to saying that the dragon is psychology: indeed, he is the psyche, he is the dark background of himself that Saint George confronts, an enemy who has already massacred many youths and maidens, an internal enemy who becomes an object of loathsome alien-ness. Is it the story of an energy projected into the world, or is it the diary of an introversion?

Other paintings depict the next stage (the slaughtered dragon is a stain on the ground, a deflated container), and reconciliation with nature is celebrated, as trees and rocks grow to occupy the whole picture, relegating to a corner the little figures of the warrior and the monster (Altdorfer, Munich; Giorgione, London); or else it is the festivity of regenerated society around the hero and the princess (Pisanello, Verona; and Carpaccio, in the later pictures of the Schiavoni cycle). (Pathetic implicit meaning: the hero being a saint, there will not be a wedding but a baptism.) Saint George leads the dragon on a leash into the square to execute him in a public ceremony. But in all this festivity of the city freed from a nightmare, there is no one who smiles: every face is grave. Trumpets sound and drums roll, we have come to witness capital punishment, Saint George’s sword is suspended in the air, we are all holding our breath, on the point of understanding that the dragon is not only the enemy, the outsider, the other, but is us, a part of ourselves that we must judge.

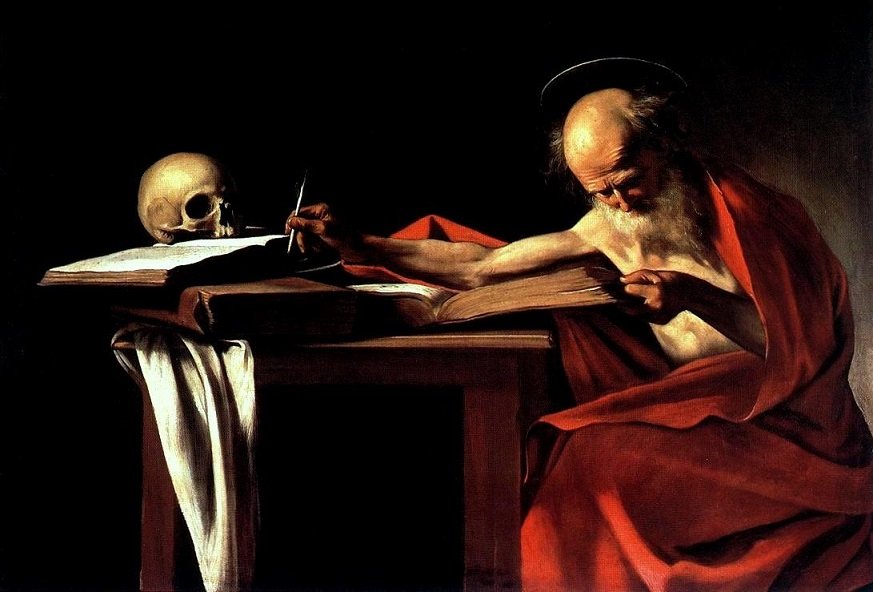

Along the walls of San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, in Venice, the stories of Saint George and Saint Jerome follow one another, as if they were a single story. And perhaps they really are one story, the life of the same man: youth, maturity, old age, and death. I have only to find the thread that links the chivalrous enterprise with the conquest of wisdom. But just now, had I not managed to turn Saint Jerome toward the outside and Saint George toward the inside?

Let us stop and think. If you consider carefully, the element common to both stories is the relationship with a fierce animal, the dragon-enemy or the lion-friend. The dragon menaces the city; the lion, solitude. We can consider them a single animal: the fierce beast we encounter both outside and inside ourselves, in public and in private. There is a guilty way of inhabiting the city: accepting the conditions of the fierce beast, giving him our children to eat. There is a guilty way of inhabiting solitude: believing we are serene because the fierce beast has been made harmless by a thorn in his paw. The hero of the story is he who in the city aims the point of his lance at the dragon’s throat, and in solitude keeps the lion with him in all its strength, accepting it as guard and domestic genie, but without hiding from himself its animal nature.

So I have succeeded in coming to a conclusion, I can consider myself satisfied. But will I not have been too pontifical? I reread. Shall I tear it all up? Let us see.

The Castle of Crossed Destinies