There are some things you tell no one, secrets packed and folded away in the far reaches of your mind — admissions of mouth herpes, for example, or athletes foot, or a night spent in jail for drunk driving. These irreversible facts, like birth certificates and blood donor cards, we keep under cover in the fireproof safe-deposit box hidden in the closet, under the Ouija board and Christmas-tree stand and the packs of Nicorette gum. Im a glutton for exhibitionism, so Id like to reveal a dirty secret: I didnt learn to read until third grade. As an elementary school kid at the Detroit Waldorf School, I was encouraged to learn at my own pace. For the uninformed, let me tell you a little about Rudolf Steiner, the founder of the Waldorf system. An Austrian philosopher, writer, and social theorist, Steiner developed an educational system that was holistic, noncompetitive, and emotionally balanced, emphasizing social health, artistic expression, and pluralism in the classroom. In practice, this meant there were no textbooks, workbooks, readers guides, or learning manuals — only paint, clay, knitting needles, and sheeps wool. I dont recall a library or a science lab in our school. There were indoor planters, pieces of felt, animal costumes, and wax paper. The classrooms were decorated with satin drapes and paper lanterns. There were no parallel walls or right angles. Quiet nooks and secret hollows were constructed in the corners, quilted blankets and hand-woven shawls held up with rocking chairs and wood broomsticks. Every room was designed to imitate a tree house or a bear cave or an underground den where foxes slept through the winter, nuzzling their young. Learning was an amorphous metaphysical experience measured by the students creative whims — beeswax one day, cotton string the next. There were no vocabulary exercises or math quizzes. The syllabus was hand drawn on the chalkboard, oil pastels in Renaissance colors simulating the seasons, sweeping rainbow illustrations of unicorns and magic owls and eavesdropping elves. The school did everything to blur all lines between fact and imagination, between art and science, between math and English, between student and teacher. For some, the disregard for standards was galvanizing. My peers took up the violin, spoke French, learned botany, identified plants and animals, mastered oil painting, weaving, and the classical guitar. But I was a slow learner, the youngest of five, easily distracted, unmotivated, listless, prone to daydreaming. I spent much of my time huddled by the radiator, keeping my beeswax warm, humming the theme to Star Search. The classrooms lack of parallel surfaces coddled me in a fluid womb of sleep and thumb-sucking. I had trouble finding the restroom, so I peed in the cot. I had trouble finger- knitting, so I balled up the yarn and used it for a pillow. I had trouble making friends, so I imagined them: Peter the ox, Dora the talking skeleton, Herb the dietician. I lived in a world of fantasy and make-believe where reading and writing were banned by laws of my own creation. Years went by — preschool, kindergarten, first grade, second grade — the dreamy sweep of a Steiner childhood. I was shuffled from calligraphy class to recorder lessons to eurythmy, with the choose-yourown- adventure of progressive schooling. It didnt matter that I was so far behind the other kids — those bold, brassy, multicultural, bilingual children with their knitted vests and viola cases. I would catch up, the teachers said. I would come around someday. I would learn to read and write by the powers of the Maypole, the winter solstice, the constellations, and Orions enchanted belt.Waldorf teachers were less concerned with literacy and standardized testing — the unpalatable concessions of the public school system — than with watercolor pencils and cotton balls. For them, the real process of learning was to be stewed and simmered in a slow cooker, or kneaded and pulled in the babys bottom of bread dough. We learned not by worksheets and chapter guides but by watching seedling trees grow from teacups, the passing of the seasons, Baroque music, folk songs, and Nordic mythology. These things poked and prodded the childs imagination, opening up vast moments of wonder, inspiring great works of art, cultivating joy, encouraging artistry and a lifetime of learning. Truth be told, I wasnt learning anything. I rode the absent-minded wave for four nebulous years, whistling and waving my way through educational anarchy. By the time I finished second grade, it was clear something was wrong. I sttill couldnt read or write. I had no friends. I had no ambitions. I was a Waldorf flunky. But by then it was too late. My parents mmmmmarriage began to crumble, along with the general downward slide of the times: Ronald Reagan, John Lennon, Mount St. Helens, to name a few. My parents started watching daytime TV, drank coffee till all hours of the night, ordered pizza, bleached their teeth, and shed their educational ideologies once and for all. They fought and kicked and threw dishes across the kitchen. Then they got divorced. That summer, I went to live with my father, who had moved to the remote upper reaches of northern Michigan, to a small logging town with a bait shop and a swing bridge and aMethodist church at the top of the hill, a quiet, historical village where people spoke with a southern drawl and wore overalls and chewed tobacco and drove tractortrailers to work at Kmart. My father apologized for everything — for Waldorf, for watercolor pencils, for recorder lessons, for est training, for past-lives séances, for macrobiotics, for pot-smoking, for the ridiculous, holistic trial and error called parenting, of which he confessed to failing greatly. “Its time you became a man,” he told me. “Its time you learned to read.” So in the beginning of third grade, I was transferred to a public school, a cinderblock prison camp with metal lockers and industrial carpeting and fluorescent lights so severe they took all color out of your complexion. Right angles abounded. Maps of the USSR. Protractors. Carbon copies. Vending machines. The sterile metal surfaces of the modern age. Computers, textbooks, worksheets, MEAP, SAT, PTA, all the formidable abbreviations of public schooling. I clawed at the classroom windows like a hamster in a glass cage, desperate for fresh air. The other children — raised on hot dogs and homogenized milk — were pig-nosed, bucktoothed, albino bullies who spent their free time at the arcade downtown playing Dig Dug or Dungeons and Dragons. But at least they could read. I couldnt even spell my own name, so I was beaten up at recess, tickled and punched behind the swings, left in a rumpled mess in the gravelly residue of the playground. After the first week of school, I was forced to take a series of multiple-choice tests — reading comprehension, basic math, language arts — each of which I failed, having artfully filled every blank with affectionate shades of the color wheel using my Swiss watercolor pencils. Thats when I was ordered to go to special ed. They sent me to a boxy trailer slumped behind the cafeteria with a stack of flash cards and a vocabulary book, highlighting useful, ordinary words that would help me navigate the everyday life of the working- class man. Apple pie. Toothpaste. Drivers license. Checkbook. Garbage can. I recognized the letters, but I couldnt piece them together into tangible, audible words. I was uninspired. “Give me a ball of beeswax,” I begged, “or a slab of clay, and I will shape the letters from the earth and choreograph a dance for each vowel while pulling the streamers of the Maypole around the schoolyard, singing the folk songs of the ancients!” My English teacher, Mrs. Lubbers, pulled me aside and said, “What is wrong with you? Are you retarded?” I shrugged and pointed at my heart, the light rhythm of hope, tapping its way out of any difficult situation. Mrs. Lubbers had the fresh face of a woman right out of a liberal arts college. She wore uneven dresses tied down with belts, and scarves dangled at every angle like those of

a heavy-metal singer. She had bobbed hair and a birthmark on her neck in the shape of an infinity symbol. She wore metal bracelets and had a firm handshake that told you she wasnt going to give up easily. At lunch, she pulled me into the teachers lounge, unpacked her lunch on the table, and made me identify each object: juice box, banana, salami sandwich, potato chips. Then she pointed out the obvious packaging. Everything was tagged with its name, in clear, concise advertising. She told me about the wonders of the industrial age, how every item of food is mass- produced, wrapped, packaged, labeled, and sold to the public with its nametag right on front: Hello. My name is________. She called the grocery store a public library, a literary adventure, a readers guide for the learning- disabled. “We are surrounded by words,” she said, as if reciting a psalm. “Its impossible not to read in this day and age. Not with all the Bazooka Joe comics lying around!” Mrs. Lubbers had devised a theory: having been rescued from the liberal clutches of Rudolf Steiner, I was like a primate, an ignorant beast of nature, a wild stallion or Frankensteins monster. I only needed the brash brainwashing of civilization, a crash course in modern society, capitalism, free enterprise, pop culture, Mickey Mouse, theHardy Boys, Ronald McDonald. I needed the chlorinated conditioning of the modern world, with its pageantry of products, its multimedia of stimulation — television, TV Guide, GI Joe, Little Debbie, Garfield, Peanuts, Cocoa Puffs. I wasnt dumb, she told me. I was just Old World, nineteenth century, understimulated. The glorious product placement of the advertising age would certainly inspire in me all kinds of wild literary exploits. Mrs. Lubbers assigned me a simple task: spend your free time at the pharmacy, the video store, or the grocery store, scanning aisles, browsing cereal boxes, examining coupons, prodding price tags and recipes for nouns, verbs, adjectives — the covert grammar of everyday objects, revealed only to the watchful eyes of the eager reader. In those quiet moments of clandestine reading I would slowly, irreversibly evolve into the acclaimed Nobel Prize–winning literary critic of tomorrow! “Read the label,” Mrs. Lubbers said, “and you will uncover the Guinness Book of World Records. Read the label and you will soon be channeling the noble intonation of Garrison Keillor, the eloquence of Vincent Price, and the brains of Salman Rushdie.” The next day was payday, shopping day. I told my father about Mrs. Lubberss homework assignment and begged him to take me to the local Super K, a commercial paradise, a library of information. He gave me a book of discount coupons to study in the car. When we got to the store, he pushed the cart from aisle to aisle and I kept my eyes open for the literature of the advertising world. Palmolive. Antibacterial. Tough on grease. I spelled out the words, shaped the vowel sounds, kept the rough edges of consonants on my tongue like a piece of hard candy. Downy fabric softener. Duracell batteries. Aspirin pain reliever. Scotch tape. These were mini-novels, micro- fiction, rousing in me the desire to read. I started with a book of matches, inspecting the small print: Close cover before striking — a mysterious line of haiku on which I meditated for hours. I sounded out the simple words on soup cans, toothpaste tubes, cracker boxes: Weight. Squeeze. Caution. Press. Warning. A simple glance at a box of Arm & Hammer baking soda beckoned the epic verse of warrior kings and rival siblings feuding for power with metal swords and battle-axes. My father gathered all the groceries like a shepherd rounding up his sheep, and I scrutinized every label with the exactness of a shearer. I read the disappointing news of the cereal box: Some settling may occur; the morbid gasps of a can of aerosol hairspray: Extremely flammable. Solvent abuse can kill instantly! A box of paper clips promised a smooth finish, much like a fine scotch. A box of business envelopes became a patriotic icon: Crafted with pride. Made in America. The standup comedy on the box of a laxative tea: Gently squeeze bag to release remaining extract. In the soap aisle, I memorized the seductive verbs on Alberto VO5s “extra body” shampoo: wet, lather, rinse. I tried to parse the mysterious ingredients on the back of the bottle, an intimidating litany of chemical compounds that might have been the recipe for an atom bomb: acetate, panthenol, sodium chloride, water. I proofread a can of Barbasol shaving cream, an erotic tone poem: “Our rich, thick lather / moisturizes and lubricates / for a clean, close, comfortable shave.” I perused the short story of the lip balm: “If irritation occurs, discontinue use.” I marveled at the absence of verbs on the Vitamin C: one tablet, twice daily; and the captivating demands on the caps of bleach: push, turn, pull, pry. Later, at home, I moved on to other documents: junk mail, restaurant receipts, speeding tickets. In my fathers messy desk drawer I uncovered a jury summons from the county clerks office in the supreme court building, a business letter creased and folded in thirds, lying next to the hole puncher. The letter was dressed with the abrupt legalities of an administrative assistant: “Read carefully. No exceptions. Dress in a manner that shows respect. If your situation prevents you from coming in person, please call.” There were unpaid phone bills, the poetry of phone numbers, first names, last names, business calls, 800 numbers. There were solicitations for credit cards, key cards, business cards, a library of area codes and office addresses. I discovered, by the book shelf, the astute astrology of my fathers record collection, as gleaned from the liner notes of a 1968 recording by Aretha Franklin, born under the sign of Aries: “You are a natural leader and your pioneering strength expresses a sincere interest in the welfare of others.” Soon I was reading whole sentences, paragraphs, pages and pages of newspapers, National Geographics, the National Enquirer, the Detroit Free Press, the New York Times Magazine, The Tibetan Book of the Dead. I took notes, made outlines, wrote thesis statements, introductory paragraphs, first drafts, revisions, ambitious dissertations on the flea circus, the shoe horn, the Sharpie, the morning-after pill, Roe v. Wade, the Interlake Steamship, the Erie Canal, the hooded sweatshirt, beeswax, the four-leaf clover, the recorder, the violin, dance theater, What I Did for Summer Vacation, Space Camp, Dance Camp, Recorder Camp, Super K, and how I heroically overcame the tribulations of illiteracy, one Snickers bar at a time. The next school day I felt like I had a hangover. I dragged myself to class with a head cold, a migraine, a fever, my right brain battling it out with my left brain, each lobe fat and fractured with all the jinglejangle of popular media. Bug-eyed, with drooping mouth, beaten but undefeated, I had triumphed over the educational armies of Rudolf Steiner and basked in the glories of commerce and capitalism, from which all knowledge thrives. I could finally read! I brought in a can of Campbells tomato soup and read every word on the label, to prove it to the rest of the class: “In a four-quart pot combine one can of soup and one can of water. Simmer over low heat, stirring often. Serve. Enjoy.” Mrs. Lubbers gave me a proud look, a row of stars, an A+, and, with a shuffling of neck scarves and metal bracelets, she handed me my very first book: Edward Gibbons Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, all six volumes, 3,568 pages. I took it home that night and read every single word.

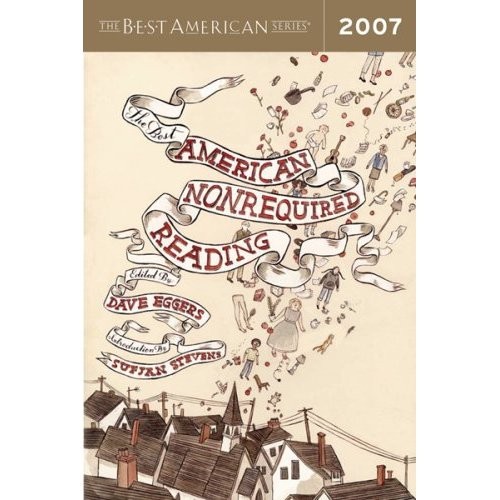

Introduction to The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2007