The end of November saw the transition from deep autumn to deep winter. Children threw snowballs. An icy chill crept under coat collars. Cars drove slowly, as if frightened of each other, the roads being now much narrower. The cold diminished, shortened, shrivelled everything. The kerbside mounds of snow were the only things to grow, and these only by virtue of the hard work and broad shovels of the clearers of courtyards and pavements.

The end of November saw the transition from deep autumn to deep winter. Children threw snowballs. An icy chill crept under coat collars. Cars drove slowly, as if frightened of each other, the roads being now much narrower. The cold diminished, shortened, shrivelled everything. The kerbside mounds of snow were the only things to grow, and these only by virtue of the hard work and broad shovels of the clearers of courtyards and pavements.

Having completed the second of Misha-non-penguin’s obelisks, Viktor looked out of the window. Today had been a day when he had neither wanted nor needed to go out. To break the silence, he switched on the set-programme speaker standing on the fridge. The carefree hubbub of parliament (plus hiss) burst forth. He turned down the volume, put the kettle on for tea, and glanced at his watch: 5.30. A bit early to be finishing for the day.

He rang Misha-non-penguin.

“All ready,” he reported. “Come and collect.”

Misha came, but not alone. With him was a little girl with round inquisitive eyes.

“My daughter,” he said. “No one to leave her with … Tell Uncle Vik your name.” He stooped to unbutton her little coat of reddish fur.

“Sonya,” she said gazing up at him. “And I’m four. – Have you really got a penguin living here?”

“You see? And she’s hardly been here a minute …” He removed her coat and helped her off with her little boots.

They went through to the living room.

“Where is he?” she asked, looking round.

“I’ll go and see,” said Viktor, but first he fetched Misha-non-penguin the two new obelisks from the kitchen.

“Misha,” he called, looking behind the dark-green settee.

Misha, standing in his hidey-hole on a treble thickness of camel-hair blanket, was staring at the wall.

“All right?” Viktor asked, stooping down to him.

The penguin stood staring wide-eyed.

Viktor wondered if he was ill.

“What’s wrong with him?” asked Sonya, having crept to join them.

“Misha! We’ve got visitors!”

Sonya went over and stroked the penguin.

“Are you feeling bad?” she asked.

Misha jerked round and looked at her.

“Daddy!” she cried, “He moved!”

Leaving them together, Viktor retired to the living room. Misha-non-penguin, deep in an armchair, was getting to the end of the second obituary. From the look on his face he seemed pleased.

“Good stuff!” he said. “Touching. Absolute shits, that’s clear, but reading this, one feels sorry for them… Any tea going?”

They moved to the kitchen, and while waiting for the kettle, sat at the table talking of the weather and other trivial matters. Tea made and poured, Misha-non-penguin handed Viktor an envelope.

“Your honorarium,” he said. “And there’s another client coming. – Oh, and you remember the one you did for Sergey Chekalin?”

Viktor nodded.

“He’s recovered… I faxed him your effort. I think he liked it… Anyway, he was impressed!”

“Daddy, Daddy,” came the little girl’s voice, “he’s hungry!”

“So he can talk, can he?” grinned Misha-non-penguin.

Viktor took cod from the freezer and put it in the bowl.

“Sonya, tell him food’s on the table,” he called.

“Hear that?” They could faintly heard her telling him. “You’re to come to table.”

The penguin arrived first, trailed by Sonya. Following him to his bowl, she watched with interest as he ate.

“Why’s he on his own?” she asked suddenly, looking up.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Viktor. “Actually he isn’t. We live here together.”

“Like me and Daddy,” said Sonya.

“What a chatterbox!” sighed Misha-non-penguin, gulping tea and contemplating his daughter. “Come on, time to go home.”

Thoroughly dejected, she left the kitchen.

“Have to get her a puppy or a cat,” said Misha-non-penguin, watching her go.

“Bring her again, to play,” Viktor suggested.

Outside, the inky blackness of a winter evening. Barely audibly, the set-programme speaker was reporting events in Chechnya. Viktor sat at the typewriter at the kitchen table, feeling lonely. He would have liked to write a short story – or a fairy story – even if just for Sonya. But filling his head was the mournful, heartfelt melody of an as yet unwritten obelisk.

“Am I ill?” he wondered, staring at the blank paper protruding from the typewriter. “No, I must, must, sometimes at least, make myself write short stories, or else I’ll go mad.”

He fell to thinking of Sonya’s funny little freckled face, her red ponytail with its elastic band.

Odd times to be a child in. An odd country, an odd life which he had no desire to make sense of. To endure, full stop, that was all he wanted.

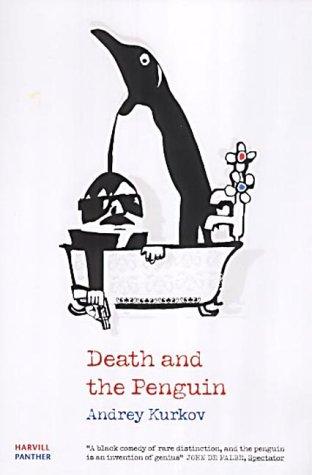

Death and the Penguin